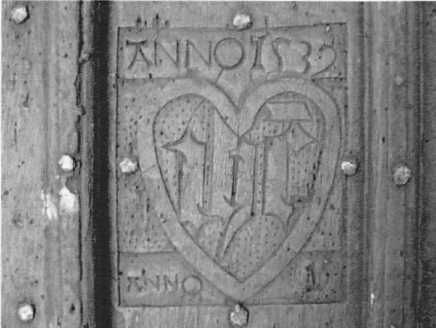

Bradney has been accused of accepting uncritically what he was told by the locals, but his accuracy in recording what he himself saw has not, we think, been questioned. Sir Joseph was in no doubt that the carving on the church door below the date 1539 was a heart containing three Greek letters signifying the name of Jesus – IHS – and he included an illustration of it in his description of the Old Church.

Why this particular symbol was chosen by the carver is not easy to determine. The heart was not a common Christian symbol in the 16th century. It appears that only two representations were recognised – the heart pierced with a sword for the Virgin and a heart enclosing the letters IHS for St. Ansanus, a 4th century martyr and patron saint of Siena. But there is no known link between Penallt and Siena. The carving could of course have been no more than a fancy of the carver. It is also possible that the monogram in the heart was added later, perhaps during the religious turmoil of the 17th century, as a sign of devotion to our Lord. Of equal interest is why the date was so emphatically recorded. It was clearly meant to be seen and remembered. It could be simply the year in which the door was newly installed; but there could be less mundane explanations. 1539 could have been the year when the parish of Trellech (in which Penallt was a chapelry) was finally released from its links with Chepstow Priory and the mother foundation at Cormeilles in Normandy. The dissolution of the monasteries lasted from about 1534 to 1540. Acts of Parliament saw first the suppression of the smaller houses and in 1539 the closing of the remaining larger and more powerful monasteries. The incumbent and/or parishioners of Penallt might have marked the event by carving the date of their “release” on the church door. But it must be admitted that this seems an extravagant gesture over what might well have been only the formal severing of what had become a pretty tenuous link.

It was in 1539 that a revision of Coverdale’s translation of the Bible into English was licensed for use by Henry VIII and in the same year an Act made it compulsory for every parish church to possess a copy of what was known as the Great Bible – although whether Penallt Old Church (being comparatively remote) actually acquired a copy in that year seems doubtful. But whatever the immediate motive, those locally who, in a period of momentous (and enforced) change, wanted to be seen to be supporting Henry’s policies could scarcely have found a better way than to carve the significant date where it could not be overlooked. Again, there was at this stage no inclination on Henry’s part to seek any renunciation of Roman Catholic dogma or ritual. This part of Wales was particularly attached to “the old religion” and the passing in 1539 of the Act of Six Articles would have been reassuring. (This Act made it penal to deny certain articles of the faith including transubstantiation.) Perhaps the Act was thought to merit special recognition and the date was intended to be a reminder to parishioners.

This splendid oak door with its ironwork, plentiful nail-heads and splits along the grain presents another problem to which, however, Bradney makes no reference. Above the heart is the bold date “Anno 1539”. Below the heart is the word Anno again and what appears to be the figure 1 surrounded by a circle of holes like those left by small nails after their removal. It could simply record the first full year of freedom from Rome’s authority (1538 was the year of England’s excommunication). It may border on the fanciful to think that this public display of support for the change of masters was a ploy to deflect official interest from Monmouthshire’s inclination to stick to “the old religion.” But no amount of head scratching has resulted in a plausible explanation so far.

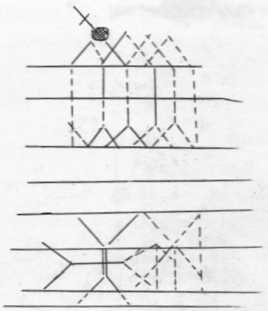

Further down still, the door bears remnants of a geometrical pattern much more difficult to see. It was about six inches square and seemingly made by a sharp knife. The vertical lines were masked by the grain of the wood but it was still possible to discern something of the original work (which may never have been completed) –when either over-zealous cleaning or an excess of preservative obliterated it. As to its purpose, other than decoration, there is no obvious answer. Some years ago, similar geometrical “scratchings” were spotted in the stonework of the building described by Major Probert in his history of Penallt of 1958 as The Great Stable at the Argoed – “one of the only two examples of an early 17th century stable in Gwent.” It was thought that this building could have been used as a chapel by the inhabitants of the vanished village of Penargelli, (allegedly in the grounds of the Argoed), for the scratchings were similar to those seen by Probert on other “barn churches.” Unfortunately, this takes us no nearer the true explanation of their origin and purpose.

Further down still, the door bears remnants of a geometrical pattern much more difficult to see. It was about six inches square and seemingly made by a sharp knife. The vertical lines were masked by the grain of the wood but it was still possible to discern something of the original work (which may never have been completed) –when either over-zealous cleaning or an excess of preservative obliterated it. As to its purpose, other than decoration, there is no obvious answer. Some years ago, similar geometrical “scratchings” were spotted in the stonework of the building described by Major Probert in his history of Penallt of 1958 as The Great Stable at the Argoed – “one of the only two examples of an early 17th century stable in Gwent.” It was thought that this building could have been used as a chapel by the inhabitants of the vanished village of Penargelli, (allegedly in the grounds of the Argoed), for the scratchings were similar to those seen by Probert on other “barn churches.” Unfortunately, this takes us no nearer the true explanation of their origin and purpose.

It has also been suggested that they were intended to warn off witches or to guard against evil spirits. Others have surmised that they are the equivalent of Masons’ marks but in wood by carpenters. These strike us as speculative indeed if only because the pattern is so complex and we have the uneasy feeling that we are unlikely ever to learn the answer to the questions raised here – unless someone finds similar survivals elsewhere and documentary evidence to explain them.

[from: Penallt Revisited]