I was extremely lucky to be taken in by the Englands. My friend, Betty was not so fortunate and was treated quite harshly by the family that had taken her in. Despite having older children of their own, Betty was the one that always had to fetch and carry from the village shop, some distance from their house. Even in the bitterest winter weather, the little six year-old could be seen struggling with heavy loads through the village back to her billet. The Englands often invited her in for a warm and a hot drink to ease her journey.

As for me, I loved Cartref and I soon became the centre of the Englands’ world. Auntie Hilda (image) was kind but strict in the Victorian way she had been brought up. I had to ‘mind my manners’ and sit up straight at the table. Even now, when I find myself slouching I remember to straighten my back and that has held me in good stead. I haven’t as yet turned into a shrinking woman. My darling mother grew smaller and smaller as she became older. Auntie Hilda remained tall and straight right up until her death at the age of eighty-eight.

As for me, I loved Cartref and I soon became the centre of the Englands’ world. Auntie Hilda (image) was kind but strict in the Victorian way she had been brought up. I had to ‘mind my manners’ and sit up straight at the table. Even now, when I find myself slouching I remember to straighten my back and that has held me in good stead. I haven’t as yet turned into a shrinking woman. My darling mother grew smaller and smaller as she became older. Auntie Hilda remained tall and straight right up until her death at the age of eighty-eight.

One of the most difficult things I had to face when I lived at Cartref was going to the lavatory in the little shed at the back of the house. It was very dark in there, even when the sun was shining. There was a wooden seat with a hole, which contained a bucket. This was covered with a wooden lid with a brass knob in the middle of it, which Auntie Hilda kept polished to a golden shine with Brasso. When you lifted the lid it was dreadfully smelly and being very small I was terrified of falling down the hole. The walls of the shed were covered with spiders’ webs and I always imagined a large spider would come crawling over me, which it never did of course. When I had to go there on dark nights, Uncle Rush would come with me with a torch and would keep marching up and down outside like a soldier on guard. Every now and again he would call out to me, “All right, our Kath? I be still here.” I can’t tell you what a comfort that was!

That first night, Gerald slept on a feather mattress in the tiny front room. I had a camp bed in Auntie Hilda’s bedroom. She put a little night light on a shelf beside me, so that I wouldn’t be frightened of the pitch dark and the unfamiliar noises of the countryside. I saw her creep into her high feather bed later, after kneeling and saying her prayers, a tall figure in a long white voluminous nightdress, some sort of cotton cap covering her head. I felt strangely reassured by her presence.

A few weeks later she changed my sleeping arrangements. The previous autumn, just after the war had started, an incendiary bomb had landed in Lone Lane, the steep road which led down to the river and the railway. There was a tinworks nearby in Redbrook, a village on the opposite side of the river. The story went that a German plane had dropped the bomb with the intention of hitting the railway or the tinworks. The only damage caused was a large hole at the side of the lane but the explosion gave the local inhabitants a fright and rumours abounded that another bomb might be dropped at any time.

Hilda, concerned for my safety, decided to make me up a bed under the solid oak dining room table in the front room. There I slept cocooned inside a cosy feather mattress for several months until all fears of further bombing had subsided. I grew to love my little hideout under the table and played there with Rono for company, imagining it was my own little house.

I can remember clearly that first warm June day in Penallt. It was a Friday, market day in Monmouth town, when Auntie Hilda took the weekly market bus from Penallt to Monmouth to do her shopping. Gerald and I stayed with Uncle Rush and Rono that first morning and discovered the four fields nearby, which belonged to the Englands. I remember the feel of the long grass against my bare legs and can visualise even now the white moon daisies with their bright yellow eyes, the buttercups, pink clover and pale blue harebells scattering the meadow where we played. Uncle Rush chopped wood in a lean-to shed with a corrugated iron roof at the bottom of the first field, while Gerald and I chased up and down with the good natured old dog joining in enthusiastically.

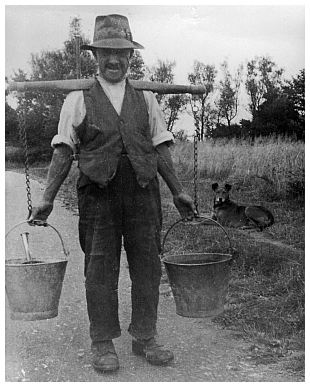

Everything we experienced that day made an impression on me. It was so different from our London life. We couldn’t turn on a tap for drinking water. Rushton went to the well at the cottage across the way and drew two buckets of water on a rope pulley from the depths of the ground (image – unknown person but from Penallt). These he attached to hooks at two ends of a wooden yoke, which he hung about his neck to carry back to Cartref. I shivered when I looked down into the dark well and saw the still and silent water gleaming way down at the bottom. “Don’t ye ever go too near the edge of the well” Rushton warned us, “It wouldn’t do for the little ‘un to fall down there now, would it?” he said, addressing Gerald. Back at Cartref, we scooped some water from one of the buckets into a cup. It had the coolest, sweetest taste, so unlike our hard London water.

Everything we experienced that day made an impression on me. It was so different from our London life. We couldn’t turn on a tap for drinking water. Rushton went to the well at the cottage across the way and drew two buckets of water on a rope pulley from the depths of the ground (image – unknown person but from Penallt). These he attached to hooks at two ends of a wooden yoke, which he hung about his neck to carry back to Cartref. I shivered when I looked down into the dark well and saw the still and silent water gleaming way down at the bottom. “Don’t ye ever go too near the edge of the well” Rushton warned us, “It wouldn’t do for the little ‘un to fall down there now, would it?” he said, addressing Gerald. Back at Cartref, we scooped some water from one of the buckets into a cup. It had the coolest, sweetest taste, so unlike our hard London water.

Rainwater was caught in a corrugated iron tank at the back of the little bungalow. This water was used for washing clothes and for all our ablutions, including the weekly washing of my hair, which when lathered with Eve shampoo left it soft, silky and shining.

When it was time for Auntie Hilda’s return from town, we walked the short distance to the crossroads to meet the market bus so that we could help carry the heavy loads of shopping back to the bungalow. Rushton took the overflowing old straw frail with rope handles, Gerald the wicker basket with two golden crusty loaves peeping out of the top and I was given the lightest thing to carry, a bundle of papers. The sun glowed warm on our backs as we walked back to the bungalow. Reaching the front door, Hilda took the papers I was carrying, unfolded them and from the middle of the bundle out fell two comics, the Dandy and the Beano. “Now then, youngsters! Take these onto the step and stay there until the table’s laid. I don’t want any arguing mind! ” We had no intention of arguing. We were surprised, as Auntie Hilda didn’t look like the kind of person who bought comics. Our Dad wouldn’t have approved. He had encouraged us to read proper books from an early age and that made the thought of looking at these comics all the more tantalising. One of them had a picture story about a wonder sheep dog called Black Bob. I thought he resembled Rono and from then on couldn’t wait to read about his adventures every week. There was also a story serial called “The Girl with the Golden Voice”, which I followed avidly until they stopped printing stories and just had the comic strips. Even Black Bob was dropped eventually, which I thought a great pity. When I returned to London at the end of the War, Hilda still bought the comics and sent them to me every week without fail. This went on for several years.

When the big old wooden table had been laid in the kitchen, we were allowed in for something to eat. I looked round the tiny room and noticed that its dark green painted walls were almost entirely covered with pictures and photographs. The one that stood out was a large framed coloured picture of three jolly looking old men each bearing a label saying “blind, deaf and dumb” with a collecting box at their feet. I think this must have appealed to Miss England’s sense of humour, though she didn’t let on, just saying to me, “Remember Kathleen, ‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’” It was some time before I realised the jolly old men were frauds. The other picture I remember clearly was a small black and white reproduction of Holman Hunt’s “The Light of the World.” Visiting St. Paul’s Cathedral after the war, I saw the original but think I preferred the little black and white one. I have no memory of any pictures on our walls at home and certainly no religious ones. Years later, when we had a more settled family home, my artist brother Gerald’s oil landscapes adorned our walls. Pictures and photographs have always fascinated me. Family photographs must have meant a great deal to the Englands as the rest of the space on the wall was taken up with them and always at the feet of a family group rested a friendly looking dog. I noticed that Rono was now tied with his lead to the leg of the table and sat quietly beneath it. “So he won’t be a nuisance while we’re eating,” said Auntie Hilda nodding at the table and beckoning to us to sit down.

A starched white cloth covered the table, which took up almost half the kitchen space. There was a plate of thinly cut bread and butter smelling fresh and new, sticky Chelsea buns and sugary lardy cakes. Even after all these years, I can still remember the spicy smell and the sweet curranty, burnt toffee taste of those Chelsea buns and what wouldn’t I give for one of those square, golden brown lardy cakes! Uncle Rush was happily sipping tea out of a mug in the shape of a smiling old fellow, bearing a striking resemblance to the drinker, the ends of whose droopy moustache dripped with tea every time he took a contented gulp. He loved tea in any shape or form. One of his odd habits, I discovered later, was to look into the big brown teapot after a meal was over. If there was any tea left, he would tip up the pot and drink the tea, leaves and all, through the spout. A few weeks later when the haymaking was in full swing in the fields near the bungalow, the refreshments Hilda brought always included a big bottle of cold tea for Rushton.

During the afternoon of that first day, Gerald was taken to the Porters’ house, a five minute walk from Cartref and by that time was not at all worried about leaving me with the Englands. The Porters’ house, similar in shape and age but slightly larger than Cartref, was at that time the village shop. Mrs Porter, a young woman about the same age as my mother, delivered the post by bicycle to all the houses around. Mr Porter worked as a miner in the Forest of Dean on the other side of the river. They had a daughter about the same age as Gerald and a son about my age. Gerald settled there happily and was well looked after. We were worried, however, at the thought of starting school on the following Monday.

[Next: the village school and the church]

[Click here for overview]