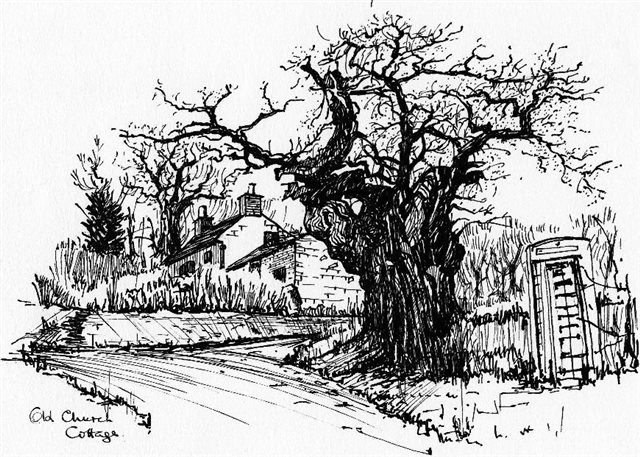

Old Church Cottage, at one time known as Church Hill Cottage, is sited on the slope above the car park at the entrance to the Old Church. The house probably dates from the middle 1700s, but as I found during the course of much needed renovation work, the house seems to have had a number of substantial alterations over the years so it is difficult to be certain.

There are records in Cwmbran which mention the existence of a public house here in 1640; quite likely, considering its location, at what would have been the heart of the old village. Perhaps the present building replaced the earlier one. It is possible that the house may have been a “church house” where “church lles” were held periodically – fund-raising events held under the authority of the Church Warden, with the brewing and baking done at the church house. There still remains a substantial bread oven on the back of the kitchen fireplace.

I find in the bundle of old deeds that the cottage and land were bought at auction in 1857 by a Mrs Mary Bagnall from a bankrupt coachbuilder for £110! The cottage later passed to Mrs Bagnall’s son-in-law, the long-serving curate of the Old Church, William Bagnall Oakeley. This is the only evidence we have of any official links with the church.

One touching piece of evidence for attachment of a more subjective kind was found when we scraped a multitude of layers of ancient limewash from the walls of the rear bedroom. On the original plaster, written in pencil was what appeared to be a lengthy eulogy of Penallt, which began “To my dear old Parish …” – but sadly this was largely indecipherable and faint.

I made a most exciting find in the main front bedroom. This room has a binder beam in the ceiling (a large beam into which smaller joists notch). A slight gap existed in between the binder and the attic floor above. In this gap I discovered a page of a letter written in sepia ink; it reads:

“Lieutenant (Lt.) same day insisted on my bringing him a towel, at which time I apply’d to be his Boy, (at which time he refused) – [crossed out] – and he answered saying he would not attend Black Whores.

On my return Lt. asked if I meant to do it, my answer to him was that having already receivd foregoing orders not to go into his cabin, I at that time thought it a duty not to Comply with at present time being engaged in taking … [lost] … belonging to the Captain.

On that Instant Lt. ordered (?) Sgt. Marines Put him in irons which was complyd with, In this predicament I remained untill Captain Dickson arrivd when he maturely (?) weighing the circumstances ordered me out of Irons.”

My impression was that this page of the letter had been hidden out of shame about the writer’s temporary disgrace. The letter was perhaps written by a junior officer on a naval vessel (the mention of a Sgt of Marines suggests this) to his parents or wife maybe?

The parchment-like paper has a watermark which says “Crompton 1797”. In 1797 Nelson played an important part in the victory off Cape St Vincent for which he was knighted. Britain was alone in fighting Bonaparte’s France that year, the year in which Nelson also lost his arm and was made a Rear Admiral. Perhaps the unknown writer was in a ship in Nelson’s fleet in the Mediterranean? It might account for the strange reference to “Black Whores”. Or perhaps he was even on a slave ship? Considering Monmouth’s naval connections it would make the hunt to trace Captain Dickson’s ship from Naval record a fascinating pursuit.

Other finds in and around the house have included a wonderfully preserved 1799 twopence piece, very old and frail pieces of cutlery, plus the usual pipe stems and bottles. There were even the leaf springs of a horse-drawn carriage in the garden .Not great treasures in themselves, but nevertheless I value the sense of place and time which these everyday relics help to foster, qualities which of course an awareness of local history can best promote.

[from: Penallt – A Village Miscellany]