The backlog of repairs after the second world war resulted in years of effort to make good the deficiencies and enhance the building’s appearance. A paragraph in the Miscellany summarised the work done over thirty years or more, much of it by parishioners bringing their skills and time to supplement the craftsmen’s work. An account from Major Probert’s pen, written in the early 80’s, provides a characteristically personal touch to understanding the scale and complexity of the problems, facing the parish – and overcome with such skill that today it is difficult to avoid concluding that “it has always looked like this.” The Major tells us what was involved.

“When we returned to Penalt shortly after the second World War the fabric of the beautiful old church was in very poor condition. We managed to get £1000 from the Pilgrim Trust and another £1000 from the County Council following upon the Disestablishment. There were many fallen roof slates and rotten battens. The wainscoting had to be removed. I refixed about 100 slates myself! The stonework inside the church was brilliant green. Having got the funds the next thing was to find an architect, as there were several other jobs needing direction beyond the capacity of a builder, such a huge bulge in the tower which required a ‘stitch’ – a very delicate operation. I was fortunate to find Mr. Caroe, the well-known expert on mediaeval churches who was already working at Llanvihangel Crucorney. We had a look inside the nave roof which was in poor condition. It was decided to have new tiles for this and to patch the chancel roof with the best of the slates. The next catastrophe was the plaster of the nave which fell – fortunately at night on an empty church. There was a splendid barrel ceiling exposed but requiring some repairs. Whilst this was being done and the scaffolding still up I though it would be a good opportunity to replace the bosses in the nave leaving the original ones still remaining in the chancel. Fortunately I had some suitable from Pembridge Castle and our then Churchwarden, Mr. Platt, turned out to be a splendid wood carver and we were able to replace the bosses in the nave. I did some – such as the intertwined fish and the pierced hands and some of the Arms of the very distinguished and Royal lords of Gwent. (It had been a Royal Manor until taken over by the Pembrokes.) We also did world events such as the ‘Comet’ and the ‘Sputnik’ and very much later, the ‘Men on the Moon’, all painted with suitable colours. No sooner had this been done than the plaster on the south aisle fell down. This we replaced with plaster board which is easily repaired. Some work on the oak framing had to be done. The leading on the west window was rotten and the glass was very broken and holed. I answered a letter in the Times from a firm in Bristol who specialised in stained glass to see if they could make a window representing St. Christopher, the travellers’ saint, and St. James the Greater. The window is to commemorate a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. The artist has depicted St. Christopher from the description of Christopher Probert’s passport to Rome in 1582, of which I have a copy. (He is buried beneath the Altar in the church. He appears at frequent intervals in the Star Chamber proceedings, usually after some considerable affray with the neighbours! He was undoubtedly recusant, but it is not known why he went to Rome. In the Llanarth papers there is a list of subscribers to the expeditions.)

The stairway up to the rood loft we unblocked and the Royal Arms which had been incorrectly placed over the chancel arch were moved to the back of the church and the plain oak cross cut from an Argoed oak replaced the Royal Arms. It was possible then to get active church members to help tidy up the churchyard which was in a very derelict state with leaning stones and many unmarked ‘tumps’ which effectively prevented cutting the grass. One side effect of this was that certain rare plants such as the black geranium flourished in parts. (Several gravestones in exotic materials with inscriptions in gilded letters have also now crept in!) The north side has now been cleared and can be used for further burials. I found the original stone altar slab of the regulation thickness (7½in.) as I suspected in the porch, where it had been placed after its removal from the proper place in the church. This was probably done after the Reformation. I found a builder to fit the frontal which I had carved from a piece of forest stone: A Chi Rho with the four Evangelist symbols – a tetraform in fact. On the advice of the Rural Dean the completed altar was placed in the South Aisle. The wall behind was stripped and replastered as also the other damp places.

I had a photostat of a picture by Mrs. Bagnall Oakley, of the interior of the church before the unfortunate ‘restoration’ of the 1880’s which shows the three-decker Jacobean pulpit which was cut down. The box pews were removed and very ordinary pitch pine pews were put in their place. Various other ‘atrocities’ were perpetrated at that time, as mentioned in my little parish booklet. At the completion of this restoration Archbishop Morriss came and blessed the stone altar, the crucifix, which had come from Santiago de Compostela, and the Virgin, which I had carved in holly and placed in the alcove where the stairs originally leading to the gallery had been opened up.”

Of course this was not the end of the story and successive years have seen old problems reappearing and new ones emerging as we tell elsewhere in this book.

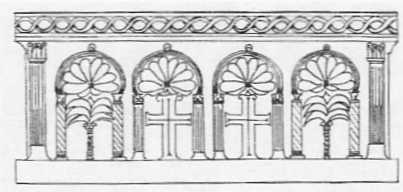

Altar front – a copy of a stone altar at Ravenna – carved during the 1914-18 war by a Belgian refugee who was chief wood carver to Malines Cathedral

[from: Penallt Revisited]