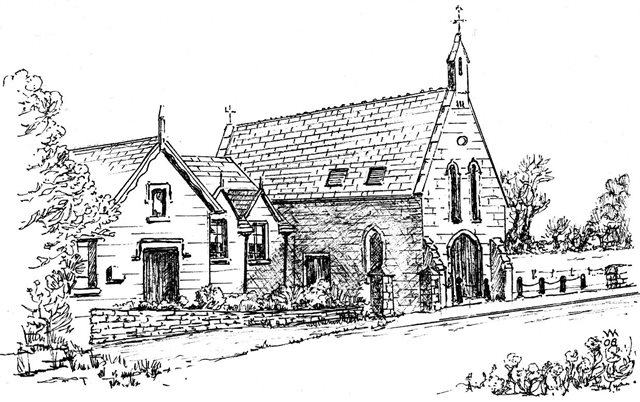

Penallt School

Penallt School could be said to have been founded in1689 by the Rev Zachary Babington who made considerable endowments for the schools at Trellech and Penallt. Trellech Church records state:

‘… at the court… held at the Gockett on 20th November in the 1st year of the reign of King William and Queen Mary … there came Thomas Roberts of the Parish of Penallt in the County of Monmouth, yeoman, and Zachary Babington of Trelleck, clerk, and surrendered … all their rights, titles etc of the mansion house, gardens, orchards and meadows… two parcells of customary lands called Croes Vane and Gworlod Mellin estimated at 10 acres…Thomas Roberts to have the use of them for his natural life and after his decease to house the free school of Penallt to instruct Children and buy books for ’em for ever…’

A fee of ninepence was paid before witnesses to have these endowments recorded correctly.

Records of education in Penallt for the 150 years between Babington’s will and the building of the school are largely non-existent, but there were probably ‘dame schools’ – elderly women who taught the children their alphabet and to count whilst minding them for a copper or two. There is some evidence of a small school near the Old Church, one in Tregagle, one near Frostlands and another near Jacob’s Ladder. Children of the wealthy were taught by the curate or a private tutor; the children of the poor picked up an education from the church, their parents and families, as best they could.

The parish magazine for December 1889 sets out a brief history of national education for the benefit of parishioners:

‘Up to the year 1832, the education of the working classes was carried out by charitable societies, of which the National Society (Church of England) and the British and Foreign School Society (Nonsectarian) were the largest. In 1832 Parliament voted a sum of £20,000 to be used in building schools in connection with these two societies, and by 1861, this grant had been increased to £840,000 per annum. However by 1870, it was found that although two million children were being educated, more than a million were still unprovided for. Therefore, in the Education Act (1870), the present system of National Education to supplement Voluntary Education, was established. It was decided that each locality should provide its own schools assisted by grants from the Government, and expenses beyond that should be paid out of the rates. School Boards were to be established in all places where the schools were not maintained properly by voluntary agencies.’

By the 19th century Babington’s house had long since disappeared into ruins, but most of the land was still held by trustees, and in 1821, a piece down by the river was exchanged with the Duke of Beaufort for another, in order to provide a central position got the school.

The parish magazine continues:

‘Until 1824, the whole of the land was let and the rent paid to a schoolmaster, but in that year he was removed and the rent accumulated until 1834 when part of the present school was built – at a cost of £83 8s 9d. The school was enlarged some years later, the money being collected by the Rev W B Oakley. It therefore appears that to 1875, the school was entirely supported by voluntary gifts. In that year Mrs Jeffreys, the school manager, applied for a Government grant under the scheme started in 1870. The Government rightly insisted that all schools to which grants were given should be efficiently run, that the buildings, books and other equipment suitable and that the children were examined once a year. The first grant was made in 1875, and the school inspected yearly but in 1877 the grant was reduced by one tenth and the payment of the whole temporarily suspended because the managers failed to carry out the inspectors’ recommendations.

‘The Government was not willing for children in one place to be less well taught than those in another on account of apathy of managers or want of funds. It has long been evident to local parishioners that it was impossible to give infants adequate teaching in a room with older children, divided only by a curtain. The teacher’s accommodation was also very poor, and so a Government letter was received stressing the necessity for another classroom and better housing for the teacher.’

The inspectors’ report for the year comments as they all seen to during this period, on the irregular attendance of the children, but adds that:

‘there is some little improvement in the style and accuracy of the work this year, but arithmetic, both on paper and oral, is weak. The room is now bright and more cheerful, but at present 27 infants are crowded into a small room 12ft by 9ft with a stone floor. The room cannot be enlarged and the only solution appears to be erection of a new classroom. Notwithstanding these difficulties, the younger children are brighter than they were last year, and give promise of making a good class under more healthy surroundings … my Lords trust that the want of increased space for the infants, as noticed by H M Inspector, will receive the serious consideration of the managers….’

The biggest consideration then, as a hundred years later when the school was closed, seems to have been a financial one. School accounts for 1889 are given as:

| Receipts:- | Expenditure:- | ||

| Govt. | £37 4s 3d | Balance Overdrawn | £ 0 5s 10d |

| School land rent | £ 6 0s 0d | Teachers’ salaries | £57 0s 6d |

| School pence | £16 7s 8d | Books, fuel, etc | £21 8s 8d |

| Subscriptions | £23 3s 0d | Other expenses | £ 3 13s 8d |

| Other sources | £ 2 19s 0d | Rent of rooms | £ 1 15s 0d |

| Balance in hand | £ 1 10s 3d | ||

| TOTAL | £85 13s 11d | TOTAL | £85 13s 11d |

Compared with other schools, Penallt was managed very economically, the average amount spent on each child in1889 being £1 11s 9d, whereas the average per head in voluntary schools for the rest of the country was £1 16s 4d, and in Board Schools £2 4s 7d. The sum involved in a Gwent primary school at the time of writing this (1988) is somewhere around £1500 per child – something like a thousandfold increase in a hundred years!

Consequently a parish meeting was called to discuss the matter of how to finance another classroom – whether the parish would agree to provide the necessary funds, or whether they should resort to the more expensive system of a School Board. The unanimous decision was that a voluntary contribution should be made by the parish, rather than that the school be placed under a Board. At a subsequent meeting, the Vicar estimated the cost of a new classroom as £90, towards which it was hoped to secure £60 from grants and subscriptions. A rate of 5d in the £ would be required the first year, and only 2d afterwards.

The work on the new classroom was planned to be completed (weather permitting) by the first week of August, 1889. Expenses were as follows:

Building contract £90; architect’s fee £5; extras for fittings £5. A total of £71 had been raised by that time, leaving £29 to be raised by voluntary rate of 5d in the £ ‘to be cheerfully paid by all, otherwise the school must be placed under a Board and the whole of the subscriptions and grants, amounting to £71, will be lost and the Parish will be saddled with a rate of at least 10d in the £ … it is most important that no single ratepayer shall set the example of refusing to contribute his share.’

The new room was completed by the early autumn and the annual visit of the inspector was awaited – parents were constantly and earnestly begged to send their children regularly to school so that the School would earn as high a grant as possible, and thus lighten the burden of expense which would fall on the ratepayers. The grant, when it came, was the highest for several years, but the inspector reported on the lack of general intelligence of the children, caused, he thought, by poor attendance. He barely passed comment on the new classroom!

Amongst the school ‘treats’ of that era was a yearly invitation to the children of Penallt, Catbrook and Trellech schools to have tea with the Russell family of Cleddon, where Lady Amberley examined them in all their subjects. One wonders whether the examination was before or after the food! From the Beacon in 1883 we learn that Mr Potter and Miss Rosalind Potter of the Argoed entertained children to tea, games, stories and fireworks. In the same year Mr Potter gave the school a lawn tennis set for the girls and a cricket set for the boys. The following year they were again given tea at the Argoed, this time by Mrs Meinertzhagen – a married daughter – and Richard Potter. In 1885 they were given buns, milk and oranges and a magic lantern show.

The school registers and log books present us with snippets of history concerning the village, Britain and the whole world. A measles epidemic in 1874 was followed by scarlet fever in 1875 and again in 1891. Parents were told in the parish magazine to ‘disinfect, clean and whitewash; to disinfect clothing and bedding, and to spread it out in the room and burn half a pound of sulphur in it, the windows and chimney being closed.’

The Relief of Mafeking in 1900 was celebrated by a half-holiday for a special tea. References to wars which must have seemed so remote to village children occur frequently, including a puzzling entry made in September 1917 which states ‘children collecting horse chestnuts to make munitions’. Another reference to the chestnuts came on November 16th – ‘the horse chestnuts which have been collected by the children have been despatched today to the Director of Propellant Supplies, London.’ Perhaps they were used as emergency ammunition for our ‘conkering’ heroes! Another log book entry from the same period (for September 10th 1918) reads ‘Yesterday the children were taken out blackberry picking in accordance with instructions received from the Director of Education and picked 100lb of fruit’ – not a bad effort for 61 children.

A more sinister weapon is in evidence in August 1939 – ‘children taken to Pelham Hall to obtain gas masks’ – and by September the first evacuees had arrived from Camden, Birmingham, West Ham and Folkeston. By July 1940, school was starting at 10 am because the children were suffering from lack of sleep caused by night raids – perhaps German bombers were shedding spare bombs after raids on Cardiff or Birmingham. The war ended in 1945 and the records show that school dinners started in November of that year. ‘School canteen starts serving dinners – first child 5d, second 4d, third 3, teachers 6d. All partake.’

In 1954 when the County Council took over management of the school it was kept in the category of ‘access by the Vicar’ and he was always a member (usually the chairman) of the Board of Trustees. In 1986, when the school closure was only a year away, the method of management was changed once more, this time to a Board of Governors. A welcome innovation was the appointment of two parent-governors – something that would seemed outrageous in Babington’s era!

It was very pleasing that Rev Babington’s money was used right up to the sad closure of the school by the County Council in July 1987. In the week that the school, closed the children were all presented with Bibles by Rev Denerley, bought with money from the Babington Trust. Although the school is now silent we hope the money in the trust fund can still be used to benefit Penallt children as Rev Babington wished ‘…for ever’.

Penallt School has closed, and many people say that once the school has gone, the heart has left the village. Not so. It is not the school buildings that makes a village what it is. It’s the people in the village and their memories. Oral history is so much more alive than that in the books and records. People in Penallt have told many stories and memories of the school and can recount tales of their fathers and grandfathers who were in the school at the time of Queen Victoria – she was, after all, only a child herself when the school was built! And so our modern children will remember their school at Penallt and pass those memories on to their children and grandchildren. Our lives are all the richer for the experience of Penallt School.

[from: Penallt – A Village Miscellany]