June 1940 – evacuation to Penallt

As far as I was concerned, life began in earnest when Gerald (my ten year old brother) and I (at the age of five and a half) were evacuated for a second time in June 1940. The memories of that day are vivid still. Paddington Station teeming with lines of schoolchildren, gas masks in cardboard boxes slung across their chests and labels printed with their names pinned to their clothes, smart or ragged as the case may be. The steam trains, their big black engines puffing out clouds of white smoke and roaring like monsters terrified me.

We had no idea where we were going. Destinations were kept secret. Our parents were not to be informed until after our safe arrival. I imagine my teacher, Miss Fraser, a young woman with a pleasant, round face, who was in charge of the small group from our school, must have had some idea of where we were bound, but, if she did, she kept it to herself. “Careless talk costs lives” the posters said.

Gerald and I managed to squeeze ourselves into a space in an already overcrowded carriage. My friend, Betty, plump and flaxen haired, just a few months older than me, was the only other girl evacuee from our school. We were the two youngest ones. A few older boys made up the rest of our party, I didn’t know then, starting out on this long journey, that this was the beginning of an experience that would change the rest of my life.

I remember going through a long tunnel and the smoky smell coming through a gap where a carriage window had been left open. The darkness was frightening and strange to me and I clung onto my brother’s hand until with a sudden whoosh, we were out in daylight again. The journey seemed endless. We changed onto a branch line train and then a smaller, diesel affair with wooden seats. Out of the dusty windows we could see wooded hills and a silver ribbon of river, which flowed along the side of the railway track until we reached a small station. White lettering on a dark brown background announced that we had arrived at the Wye Valley town of Monmouth, the birthplace of King Henry V. I think someone must have met us there. We were led through a white picket gate out of the station, through a coal yard and onto a road leading out of the town. I have dim memories of walking down a driveway to a large house and being given tea and cakes. It was rather institution like and I feared that this was where we might end up.

However, the large house was not to be our final destination. We were taken on a rackety old bus up a winding road, its engine wheezing its way up a steep hill above the town with glorious views towards the Brecon Beacons. I had never seen anything like it, though by this time I was too weary to take much account of my surroundings. Shadows had begun to darken the summer evening when we stopped outside a barrack like building with an arched corrugated iron roof. “I think this must be Pelham Hall,” (image) Miss Fraser informed us.

Inside, blackout curtains had been drawn across the windows and oil lamps hung from the ceiling giving a strange, ghostly light onto the heads of the people sitting on chairs all around the room. There were some important looking people sitting at a table on a small stage at the far end of the hall. One of these was the billeting officer, who began ticking off the names on her list. My friend, Betty, was soon taken off to her new home. Then, one by one, the boys were found billets, many with local farms. Gerald was still clinging onto my hand and protesting that Dad had said we were to stay together. I think we must have caused the billeting officer a bit of a headache. In the end, a tall, woman dressed in a long old fashioned coat and a hat shaped like a square, flat flower pot squashed over a grey bun, came to our rescue. She had a rather stern expression but when she spoke her voice was soft with a countrified accent that was half sing song welsh and half West Country. It was the distinctive border accent of Monmouthshire. “I’ll take both youngsters for tonight,” she said. “Tomorrow the lad will see he won’t be far away with Mrs Porter at the shop just along the road.” Miss England had asked particularly for the youngest little girl but certainly not a boy! “That’s very good of you, Miss England,” said a distinguished looking older man, who sounded posh like the people I’d stayed with in Suffolk. I noticed he was very respectful to Miss England and I was soon to find out that most people when in her presence treated her with the utmost deference. When I read David Copperfield a few years later, I thought she was a lot like Betsey Trotwood.

Inside, blackout curtains had been drawn across the windows and oil lamps hung from the ceiling giving a strange, ghostly light onto the heads of the people sitting on chairs all around the room. There were some important looking people sitting at a table on a small stage at the far end of the hall. One of these was the billeting officer, who began ticking off the names on her list. My friend, Betty, was soon taken off to her new home. Then, one by one, the boys were found billets, many with local farms. Gerald was still clinging onto my hand and protesting that Dad had said we were to stay together. I think we must have caused the billeting officer a bit of a headache. In the end, a tall, woman dressed in a long old fashioned coat and a hat shaped like a square, flat flower pot squashed over a grey bun, came to our rescue. She had a rather stern expression but when she spoke her voice was soft with a countrified accent that was half sing song welsh and half West Country. It was the distinctive border accent of Monmouthshire. “I’ll take both youngsters for tonight,” she said. “Tomorrow the lad will see he won’t be far away with Mrs Porter at the shop just along the road.” Miss England had asked particularly for the youngest little girl but certainly not a boy! “That’s very good of you, Miss England,” said a distinguished looking older man, who sounded posh like the people I’d stayed with in Suffolk. I noticed he was very respectful to Miss England and I was soon to find out that most people when in her presence treated her with the utmost deference. When I read David Copperfield a few years later, I thought she was a lot like Betsey Trotwood.

We followed Miss England out onto the dark, country road, silhouettes of trees and hedges showing up in the moonlight. It was deadly quiet and when an owl hooted as we passed a tall tree, I jumped in fright never having heard such an eerie sound before. We must have walked for about ten minutes or so, past a few scattered buildings until we reached a little wooden gate painted white set within a stone wall. There was a long path leading up from it through a garden with what appeared to be a vegetable patch on one side and a flower border on the other. The intense scent of sweet peas filled the air. Halfway up the path we went through a rustic wooden arch. “Don’t get caught up on the ramblers,” Miss England warned us. “They be a bit thorny and do spread themselves all over the place. But you’ll see how pretty the little pink roses are in the morning.”

We reached the front door of a small, neat white and brown bungalow (image). It had the look of a doll’s house with its square shape, a window either side of the front door and a chimney pot stuck in the middle of the roof. The black knocker on the white front door was in the shape of a dog with floppy ears. It is still there to this day. Miss England opened the door and a black and white collie pushed his way out and greeted us, his tail wagging furiously. I hid behind Miss England’s long black coat afraid that he would knock me over. “This is old Rono. Don’t be afraid. He be very friendly, just pleased to see you, that’s all.” I thought Rono a very strange name. I found out that the ‘no’ bit stood for November, the month of his birth. What ‘ Ro’ stood for I either never discovered or have quite forgotten..

We reached the front door of a small, neat white and brown bungalow (image). It had the look of a doll’s house with its square shape, a window either side of the front door and a chimney pot stuck in the middle of the roof. The black knocker on the white front door was in the shape of a dog with floppy ears. It is still there to this day. Miss England opened the door and a black and white collie pushed his way out and greeted us, his tail wagging furiously. I hid behind Miss England’s long black coat afraid that he would knock me over. “This is old Rono. Don’t be afraid. He be very friendly, just pleased to see you, that’s all.” I thought Rono a very strange name. I found out that the ‘no’ bit stood for November, the month of his birth. What ‘ Ro’ stood for I either never discovered or have quite forgotten..

We went along a short narrow red and black quarry tiled passage into a small kitchen, its stone floor partly covered with some coconut matting. There was a black iron grate with a shiny black oven at the side of it. Sitting on an old horsehair sofa with the stuffing escaping from it sat an old man with white silky hair and a white droopy moustache. He looked Gerald and me up and down with a most amiable expression. Turning to Miss England he said “Well, I’m blowed Hildy, you’ve brought home two of ‘em then!” Miss England sniffed, “Just for tonight. The young lad wouldn’t leave his sister. He’ll be all right when he sees how near at hand he’ll be with Mrs Porter. We’re keeping the little girl, Kathleen.” She introduced the old man as her brother, Rushton. “Now then, Rush! Get the cocoa on the go. These two be tired out!”

Another strange name – Rushton! His full name was Rushton William Gardner England. It seems he was named after a Mr Rushton, a greatly respected gentleman for whom his mother had worked in service in her youth. She was then Mary Ann Gardner and gave her first-born the addition of her maiden name. A few days later I was calling the pair Uncle Rush and Auntie Hilda as though I had known them all my life.

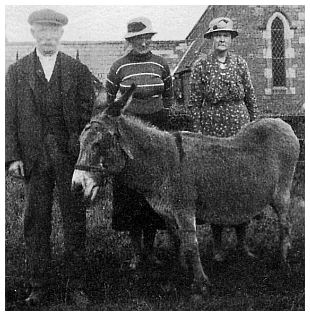

Hilda Helen England had been a lady’s maid of a most superior kind. Her ladylike demeanour, sewing and crochet skills and the ability to produce the daintiest plate of waver thin bread and butter anyone had ever seen, made her a firm favourite with her employers. Her parents, Mary and Edwin England had worked for the Pelhams, who had lived for many years at Moorcroft House in the parish of Penallt where the Englands had been born and bred. The Pelhams were Fabians and there were many interesting visitors to their grand house when Hilda was a young woman, including the writers Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells. Hilda entered service as a young girl and worked at both the grand houses in Penallt, the other even grander house being The Argoed, dating back to the 17th Century. Hilda told me that she remembered seeing Bernard Shaw there when she entered a room with a tray of tea. “He didn’t even look up! Just looked at his shoes. I thought he was very rude.” She was not in the least intimidated by the great man, just annoyed at his bad manners. The last nine years of her life in service were spent at Cadogan Square in London working for Lady Alice Mann until family commitments brought her back home. I later found out that Hilda loved London and would have made it her home had circumstances been different.

Rushton was the oldest child of the England family. He was born on October 31st 1870 in an area called The Birches. He told me that as a new born baby he had been put through a hollow oak twelve times to keep away the evil spirits that abounded on Halloween. This is what his mother, Mary Anne, who was supposed to have second sight, told him.

Rushton had been apprenticed as a boy to learn the printing trade at the offices of the local newspaper The Monmouthshire Beacon, still going and widely read locally today. In all weathers, he walked the four and a half miles of footpath through fields and woods down to the town and back every working day for the next fifty years. He was well regarded as a compositor and was an industrious worker until new machinery and methods caused him to become redundant in the early 1930’s. There was no redundancy pay or pension in those days. It must have been a bitter blow to lose his job after all those working years. When Hilda returned home after the death of her parents, she and Rushton had the small bungalow built on some land they owned and named it Cartref, the welsh word for ‘home’. Neither of them had ever married. Rushton had lived at home and looked after his parents until they died. Two brothers, Joseph and David, went to Canada to find work. Ted, the second eldest had married but was childless. His wife, Lucy had delicate health and died shortly after my arrival in Penallt. There was another sister, Mamie, a little older than Hilda, who lived a few miles away in a place called New Mills with her bad tempered second husband, Albert. Mamie, in photographs I had seen of her as a young woman must have been very beautiful and still retained traces of that beauty as an older woman. However, she was very unfortunate in her marriages. Her first husband died on their honeymoon and something very dramatic happened to Albert soon after my arrival in Penallt- but more of that later.

The two youngest sons, Arthur and Robert, always referred to as Art and Bob, died at the beginning of 1918. Arthur had been a driver of horses during the First World War, taking guns and ammunition to the Front, an extremely dangerous occupation. He was discharged from the Army in 1915 “suffering from sickness”, – post-traumatic stress disorder, I wonder? From the stories Hilda had told me, the brothers were very close. Robert, I believe suffered from tuberculosis and died shortly after his brother. Penallt lost ten of its young men due to the First World War, a large number for such a small community, as it was in those days.

[Next: Cartref and the Englands]

[Click here for overview]