Penallt in 1894

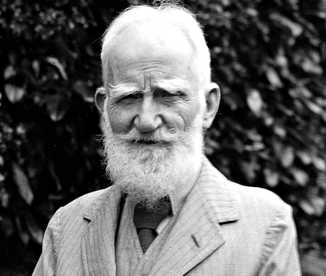

The following article was written by George Bernard Shaw, in his capacity of Music Critic, when he attended a village concert in Penallt School in 1893, during one of his frequent visits to the Argoed:

10 January, 1894

‘I am, I suppose, in the west country, by which I mean generally any place for which you start from Paddington. To be precise I am nowhere in particular, though there are ascertained localities within easy reach of me. For instance, if I were to lie down and let myself roll over the dip at the foot of the lawn, I should go like an avalanche into the valley of the Wye. I could walk to Monmouth in half an hour or so. At the end of the avenue there is a paper nailed to a tree with a stencilled announcement that the Penallt Music Society will give a concert last Friday week (I was at it, as shall presently appear); and it may be, therefore, that I am in the parish of Penalt, if there is such a place. But as I have definitely ascertained that I am not in England either ecclesiastically or for the purposes of the Sunday Closing Act; as, nevertheless, Wales is on the other side of the Wye*; and as I am clearly not in Ireland or Scotland, it seems to follow that I am, as I have honestly admitted, nowhere. And I assure you it is a very desirable place – a land of quietly beautiful hills, enchanting valleys, and an indescribable sober richness of winter colouring. This being so, need I add that the natives are flying from it as from the plague? Its lonely lanes, where, after your day’s work, you can wander amid ghosts and shadows under the starry firmament, stopping often to hush your footsteps and listen to a wonderful still music of night and nature are eagerly exchanged for sooty streets and gas lamps and mechanical pianos playing the last comic song but two. The fact is, wages in the district do not reflect the sufficiency of the scenery: hence ambitious young men forsake their birthplace to begrime themselves in “the tinworks,” symbolic of the great manufacturing industries of the nation, which have all, figuratively speaking, the production of tin as their final cause. I cannot walk far without coming upon the ruins of a deserted cottage or farmhouse. The frequency of these, and the prevalence of loosely piled stone walls instead of hedges, gives me a sensation of being in Ireland which is only dispelled by the appearance of children with whole garments and fresh faces acquainted with soap. But even children are scarce, the population being, as far as I can judge, about one-sixth of a human being per square mile.’

There is a band in this place. Two little cornets, four baritone saxhorns, and a euphonium, all rather wasted for want of a competent person to score a few airs specially for them; for the four saxhorns all play the same part in unison instead of spreading themselves polyphonically over the desert between the cornets and the tuba. When their strains burst unexpectedly on my ear on Christmas Day, I supposed, until I went cautiously to the window to reconnoitre, that there were only three instruments instead of seven.

‘With a parish organist to set this matter right for them, and a parish bandmaster to teach them a few simple rules of thumb as to the manipulation of their tuning-slides, the seven musicians would have discoursed excellent music. I submit that, pending the creation of a Ministry of Music, the Local Government Board should appoint District Surveyors of Brass Bands to look after these things. There are also carol singers; but of them I shall have nothing to say except that the first set, consisting of a few children, sang with great spirit a capital tune which I shall certainly steal when I turn my attention seriously to composition. The second set came very late, and had been so hospitably entertained at their previous performances that they had lost that clearness of intention and crispness of execution which no doubt distinguished their earlier efforts.

‘But the great event of the Penalt season was the concert. It was taken for granted that I, as an eminent London critic, would hold it in ineffable scorn; and it was even suggested that I should have the condescension to stay away. But, as it happened, I enjoyed it more than any native did, and that, too, not at all derisively, but because the concert was not only refreshingly different from the ordinary London miscellaneous article, but much better. The difference began with the adventurousness of the attempt to get there. There were no cabs, no omnibuses, no lamps, no policemen, no pavement, and, as it happened, no moon or stars. Fortunately, I have a delicate sense of touch in my boot-soles, and this enabled me to discriminate between road and common in the intervals of dashing myself against the gates which I knew I had to pass. At last I saw a glow in the darkness, and an elderly countryman sitting in it with the air of being indoors. He turned out to be the bureau, so to speak; and I was presently in the concert-room, which was much more interesting than St James’s Hall, where there is nothing to look at except the pictures of mountain and glacier accidentally made – like faces in the fire – by the soot and dust in the ventilating lunettes in the windows. Even these are only visible at afternoon concerts. Here there was much to occupy and elevate the mind pending the appearance of the musicians; for instance there was St Paul preaching at Athens after Raphael, and the death of General Wolfe after West, with a masonic-looking document which turned out to be the school time-table, an extensive display of flags and paraffin lamps, and an ingenious machine on the window-blind principle for teaching the children to add up sums of money of which the very least represented about eleven centuries of work and wages at current local rates.

‘The program shewed how varied are the resources of a country parish compared to the helplessness of a town choked by the destiny and squalor of its own population. We had glees – ‘Hail Smiling Morn’, ‘The Belfry Tower’, etc. –by no means ill sung. We had feats of transcendent execution on the pianoforte, in the course of which Men of Harlech took arms against a sea of variation, and, by opposing, ended them to the general satisfaction. But it was from the performances of the individual vocalists that I received the strongest sense that here, on the Welsh border, we were among a naturally musical and artistic folk. From the young lady of ten who sang ‘When you and I were young’, to the robust farmer-comedians who gave the facetious and topical interludes with frank enjoyment and humour, and without a trace of the vulgarity which is the heavy price we have to pay for professionalism in music, the entertainment was a genuine and spontaneous outcome of the talent of the people. The artists cost nothing; the pianoforte-tuner, the printer, and the carpenter who fixed the platform can have cost only a few shillings. Comparing the result with certain of the “grand concerts” at St James’s Hall, which have cost hundreds of pounds, and left me in a condition of the blankest pessimism as to the present and future of music in England, I am bound to pronounce the Penalt concert one of the most successful and encouraging of the year.

‘When the concert was over and we all plunged again into the black void without, where we jostled one another absurdly in our efforts to find the way home, I had quite made up my mind to advise all our fashionable teachers of singing to go to the singers of Penalt, consider their ways, and be wise.

*It seems that Shaw was even more confused as to his exact location than he thought. As he wrote this piece from Penallt, why ever did he think that Wales is on the other side of the Wye’? Over there was, and still is, Gloucestershire!

[from: Penallt – A Village Miscellany]