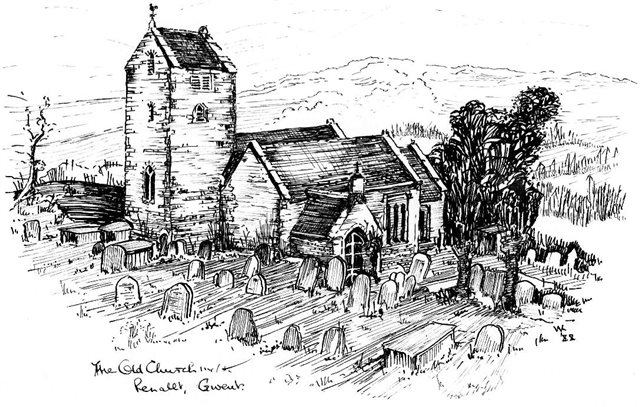

The church is the focal point of a parish, and especially of a rural parish, even for those who rarely or never worship in it. Often visible for miles around, it is a geographical as well as a spiritual centre, the hub and rallying-point of its community. This commanding central presence is well seen in the neighbouring parishes of Trellech and Cwmcarvan, but Penallt’s terrain is too steep and wooded and its habitations too scattered to permit this visual role. Indeed our church seems as though deliberately set apart, secluded among woods at one end of the parish, like a hidden sanctuary only reached by an effort on the part of the seeker. Nowadays we drive there in our cars, but for most of its existence many parishioners had a long walk to get to church.

Despite the building of St Mary’s in 1869 as a chapel to the village school, and its regular use ever since as a chapel of ease near the centre of the parish, what we call the Old Church has continued to exert a sort of hidden power as the community’s ancient focus, its hallowed spot. It is the first place an inhabitant of Penallt will tell a visitor to go and see, a source of local pride, ‘something special’. And visitors are indeed impressed, often captivated, by the serene and simple beauty of the church in its incomparable setting, high up on a green hillside that plunges hundreds of feet to the River Wye below.

The steep rustic graveyard is the resting-place of generations of both church and chapel people; and still today even those who rarely entered the church in their lives are brought after death for the funeral service to be read over them and for their relatives and friends to gather, often in great numbers, to pay their last respects. Within living memory the corteges still came on foot, the coffin borne on neighbours’ shoulders. Small wonder that it was customary to stop for a ‘blow’ at the site of the ruined cross at the top of the steep climb up from the Black Brook valley; this has sometimes been given the curious name of Cross Vermond, probably by association with the ancient (but now vanished) Vermin Oak nearby, where tradition has it that the last wild boar in the district was killed.

About the foundation and early history of our parish church we know very little; even the saint to whom it was presumably dedicated is forgotten (a very unusual circumstance), although St Michael was often invoked as protector of hill-top churches, especially if the need was felt for a watchful eye to be kept on an old site of pagan worship! The site is believed to be an ancient holy place, and there is an old well beside the once-frequented path to Troy and Monmouth, just beyond the churchyard wall, which it is thought may once have served an early hermit’s cell or an even earlier pagan shrine.

Many Welsh churches are known to be built on ground first sanctified by the residence of a saint or a hermit. Indeed, when it was decided to build a new church, a revered holy man would often be asked to come and dwell at the spot and hallow it by forty days of prayer and fasting; churches dedicated to such early saints as Cattwg, Teilo, Dubricius or Dingad may well have been founded in this way. But although many parish churches in our area have probably existed continuously since their early foundation, in other and perhaps more sparsely inhabited places the people’s spiritual needs continued to be met by resident hermits or by itinerant priests and friars. Some of the wayside crosses whose bases survive, or whose existence is recorded only by a name, may date back to those distant times as places where open-air services were held (though others are of a later mediaeval date). In forested districts such as the Wyeswood and the Forest of Dean, only settled in later ages, the formation of new parishes continued until quite recent times: Whitebrook, Catbrook and Devauden are examples of this, as well as Redbrook, Clearwell and others in the Forest.

With the coming of Norman rule, which was firmly established in our area only after 1150, the Church was more fully organized into parishes and dioceses to harmonize with the feudal system of land tenure (of which the monasteries and their lands were an increasingly important part). Trellech, which included Penallt, was at first a Royal Manor, but during the 12th century the lordship passed first to the de Clare family and later to William the Marshal, first Earl of Pembroke. It was probably Gilbert de Clare or his son Richard who first undertook the building of a church at Penallt, which is listed in a document believed to date from the early 13th century as belonging to the Benedictine Abbey of Cormeilles, near Brionne in Normandy, and to its daughter foundation of Chepstow Priory. Cormeilles Abbey had been founded in 1060 by William FitzOsbern, cousin of the Conqueror and the first Norman Lord of Chepstow; and it is from the same district of Normandy that a remarkable testimony has been preserved to the religious fervour and enthusiasm which was engendered in that age of faith as the building of a new church. It is contained in a letter from the Abbé Haimon to members of a religious community in Staffordshire, describing the building of his own church, and it reads in part as follows:

“Who has ever seen or heard of such doings? Princes, men powerful and rich, nobly born women, proud and beautiful, lean their shoulders to the yokes of the carts which transport the stones, the wood, the wine, yeast and oil, the lime and all that is necessary for the construction of the church and the subsistence of those who work there …

Amongst the crowd, which advances with effort, a profound silence reigns, so emotional is the atmosphere. At the head of the cortege the high minstrels sound their trumpets of copper and the holy banner of brilliant colours wave in the wind. No obstacle, no ruggedness of mountains, no depth of water are able to stop the march …

When they arrive near to the foundations of the church the carts are ranged round it as if it were a camp. From twilight to dawn canticles are sung; the carts are lit by the red light of torches. And in this night many miracles occur: the blind recover their sight, the paralysed walk.”

We might be tempted to think that the good Abbé was exaggerating a little in his enthusiasm were it not for evidence of comparable scenes of collective devotion and effort in other places at that time. Perhaps our own church was built in this way – though at least the stone and timber would not have had to be carried very far.

The oldest surviving parts of the church are considered to be about a century later than the probable date of foundation; the first church built on the site was perhaps only a wooden construction. An authoritative account of the main features of the building, and their ages, is given by the architect, A. D. Caroe, as quoted in Major Probert’s booklet about the parish published in 1958:

“In the churchyard are the base, socket stone and lower part of the shaft of a magnificent 15th century Cross. The Cross itself was probably destroyed at the Reformation. There is a very ancient yew, somewhat hollow, but still flourishing. In the porch is a holy water stoup intentionally broken. Tradition says that this was broken by the 17th century Puritans, but this wretched iconoclasm had been going on ever since the Reformation.

On the door itself is carved the date 1539. A particularly attractive sight greets you, on entering, of the roughly moulded nave arcade built by unlettered masons of the 15th century. The fluted pillars are set diagonally.

On the door itself is carved the date 1539. A particularly attractive sight greets you, on entering, of the roughly moulded nave arcade built by unlettered masons of the 15th century. The fluted pillars are set diagonally.

The tower appears to be the earliest part of the present structure, dating from the end of the 13th century, though the chancel arch and parts of the north nave wall (which are almost devoid of architectural features) may be contemporaneous. The tower originally had a high pitched roof running east and west, the north and south walls having been raised after the Reformation, no doubt in order to accommodate the four bells.

The south aisle wall contains 15th century windows. A pleasing diagonal passage gives a view of the high altar from the south aisle. This is probably a later addition, but still mediaeval.

It seems as though the nave roof must have been lowered at some time, as there are two small blocked windows which are clearly designed to light the rood screen, this latter having been removed and destroyed by the iconoclasts, probably during the Reformation.”

In fact the Reformation came to this area with less turmoil than in many other places – in part, perhaps, because the Welsh church seems always to have maintained a certain aloofness from both Rome and Canterbury, and a powerful memory of its ancient Celtic origins and its local saints. And indeed, the older rite persisted here for a long time, especially among the gentry, although subject to gradually increasing persecution: near the end of Elizabeth’s reign it was reported that the county of Monmouth had the highest proportion of Recusants of any part of the kingdom. This was probably due to the fact that the Earls of Worcester, the most powerful local family, managed by consummate diplomacy to remain Roman Catholic without forfeiting their position and influence. Under their protection many of the lesser landowners and some of their tenantry were able to maintain the Roman rite in the privacy of their household chapels; these may have included Christopher Probert of Pantglas and the Argoed, though if so, he kept his allegiance secret.

In the 17th century the Puritan movement and the Civil War raised religious tensions to a new pitch. The Vicar of Trellech was ejected, after only one year in office, on the restoration of Charles II, no doubt for Puritan tendencies; on the other hand ‘no popery’ hysteria a little later led to the seizure in the Monmouth area of some of the last Catholic martyrs. A reaction followed, and the Church sank into a somewhat lethargic state in the 18th century until the Wesleys once more revived religious fervour, leading not only to the hiving off of the Methodists but to a renewal of both devotion and debate within the Anglican communion.

At the same time there was developing an awareness of the aesthetic and cultural value of the monuments of the past, first articulated by the Romantic movement in literature and the arts. This, coupled with the growth of the educated middle classes and the increasing wealth of the country, led to concern over the physical condition of our ancient churches, many of which had over the centuries fallen into a sad state of decay: the age of restoration had arrived. Some of the restorers were undoubtedly both over-zealous and insensitive, but in many cases the state of the fabric may have made virtual rebuilding necessary; in Penallt the alterations were far less drastic and have not spoilt the essential character of the church. There is no doubt that without the Victorian restorations many parish churches would eventually have become ruined and abandoned, and this might have happened in Penallt after St Mary’s was built if the Curate, the Rev. William Bagnall Oakeley, had not a few years earlier undertaken a personal campaign to raise money for repair of the Parish Church.

In June 1865 the Monmouthshire Beacon carried a notice appealing for funds for this purpose. What is most interesting is that his intention was not only to restore but to enlarge the church; he wanted to add a north aisle to match the existing one on the south. This, of course, was never achieved, but it is remarkable that the church was not considered large enough to hold the congregation at that time – a sobering thought today. Part of Rev. Oakeley’s appeal is worth quoting for the light it sheds on the state of affairs at that date;

“The parish church of Penallt, near Monmouth, is in such a state of dilapidation that it is in parts unsafe; it is, therefore, necessary to take immediate steps for its early restoration. It is also proposed to add a new North Aisle. The parish is composed almost entirely of Farmers and Agricultural Labourers and little aid can be looked for from them. The Curate, therefore, makes this appeal to the friends of the Church in hope of obtaining assistance to complete the proposed Restoration. The estimated cost is £600 (exclusive of the Chancel).”

He goes on to indicate that the Duke of Beaufort and he, himself, had each promised £100 towards the total; his wife, as well as being a talented painter of landscapes, was a wealthy women, and it was probably with her money that he had been able to build Moorcroft (or Snakescroft, as it was called at that time). But the failure to create the north aisle (perhaps a blessing in disguise) suggests that the response to his appeal was disappointing; or did the estimate prove unrealistic, as is not seldom the case?

It was thought necessary, only twenty years later, for a more thorough restoration and redesigning of the interior to be undertaken and this was done in 1886 at a cost of £300, with additional refurbishment and decorations subscribed by various donors. What is most remarkable is that the whole of the principal cost was met by Mrs. Gosling of Wyesham House (at a time, it may be added, when Dixton parish was struggling to raise money to pay for the church recently built at Wyesham); no doubt she could see Penallt Church across the river from her home and had grown very fond of it. She was the wife of Henry Gosling, one of the partners in Bromage and Gosling’s Bank, which occupied what is now the part of the Kings’ Head Hotel to the left of the entrance in Agincourt Square; it was later taken over by Lloyd’s Bank whose initials L.B. and the date 1894 can be seen moulded on the handsome guttering.

It is interesting to note that Richard Potter of the Argoed had contributed generously to Dixton parish funds a year or two earlier, principally for its Workhouse, which probably took in destitute people from Penallt; so Mrs Gosling’s munificence may have been in part a return gesture. Mr Potter was, of course, a great benefactor of Penallt; he was very active in its elevation to a separate parish independent of Trellech, and largely paid for the building of the vicarage in which the Rev Richard Goldney took up residence in 1888.

The principal items of work carried out in 1886 by the Monmouth builder David Roberts were:

- strengthening the walls by excavating and infilling with concrete to a depth of three feet;

- rebuilding the north-west corner buttress;

- relaying the floor on a continuous slope, eliminating the steps down to the chancel;

- piercing an additional window in the south aisle wall;

- removing the large gallery from the nave;

- replacing the box pews with the benches we have today;

- and lowering the Jacobean three-tier pulpit to its present height.

“How quaint and old-fashioned the Parish Church is may be derived from the fact that there is no sort of illuminant in nave, chancel or aisle. Services are never held there at night during the winter.

Occasionally late in September, when days are getting shorter, if the weather is overcast or the sermon unduly long, the last hymn is sung more from memory than book. The candles on the Holy Table and Pulpit and Reading Desk, instead of giving light, seem only to intensify the darkness.”

This deficiency was made good after the Second World War with the installation of electric light, and in the following years many other improvements were made, largely through the generosity of individual parishioners, but with help from the Pilgrim Trust and the diocese. They included:

- the re-roofing of the nave and tower with tiles in place of the old slates;

- the installation of an electric organ to replace the harmonium, and of gas-fired radiators;

- the erection in the south aisle of an altar comprising the stone slap which had covered the original chancel altar, long since replaced and abandoned, with a new frontal carved in stone by a parishioner;

- the formation of a vestry by placing a wooden screen across the base of the tower;

- restoration of the ceilings, with the provision of new carved and painted bosses (including one of the Sputnik, a comet and men on the moon) in the nave, in keeping with the original once in the chancel;

- numerous additions to the furniture and adornments; and

- repairs and embellishments to some of the windows.

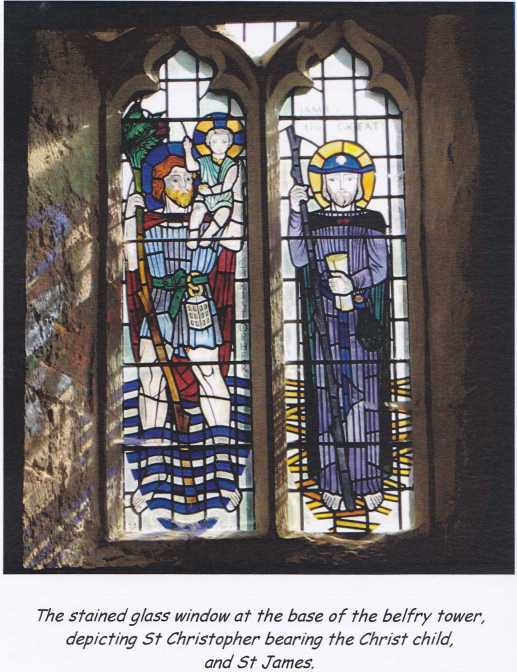

These included the installation in the vestry of a find stained-glass window depicting Saints James and Christopher, the patrons of pilgrims and travellers. This was intended to commemorate the fact that Penallt, overlooking the Wye, stands on what was one of the mediaeval routes to Compostella for pilgrims from Britain, many of whom took ship for Spain from Bristol. St James is seen garbed as a pilgrim in accordance with the passport description of Christopher Probert, who died in 1622 and is buried in front of the altar.

The Royal Arms were restored, repainted and rehung as a Silver Jubilee gesture. They are the arms of Queen Anne, who reputedly had stayed at Troy house.

The maintenance of old buildings is a never-ending responsibility, and in recent years further extensive work has been found necessary, particularly for the preservation of the chancel roof, the timbers of which were badly weakened by woodworm and rot. The cost of such work, involving the replacement of main timbers, would have been far beyond the resources of the parish if we had not had the good fortune to be able to employ the Manpower Services Commission, whose team of young trainees supervised by craftsmen did the work free of charge, leaving only the cost of materials (in itself a large amount) to be met from parochial funds. It was thus possible to complete the work by roofing the chancel with tiles to match those already laid on the nave and tower.

As part of the same overall programme the M.S.C. also undertook extensive improvements in the churchyard: repairing the lychgate; rebuilding large sections of the boundary walls, together with clearance of encroaching saplings and brambles; raising fallen and leaning headstones and levelling some of the unidentified grave tumps; clearing away rubble, improving drainage and so forth.

Meanwhile, the gravel path from the lychgate, which had become badly eroded, was relaid in paving at a parishioner’s expense; and the lime trees which lined the path, most of which were slowly rotting, have been felled and replaced by young ones.

Even more recently, thanks to a very generous bequest in the will of a well-wisher, further work has been carried out or is planned. The timbers of the nave roof have been treated against insect and fungus damage, a modern heating system has been installed and repairs are in progress to some of the pews. Thus, we hope that we can hand on to future generations of Christians in Penallt the priceless heritage of our parish church in a sound condition to serve as a place of worship, and to the wider community one of the most notable monuments of our mediaeval past in this area.

PARISH CHURCHES

“In a wonderfully large proportion of the parishes throughout the country the church is the embodiment of that historical continuity of which our race is justly proud. Here the future finds its most striking expression and is treasured by men of widely different sympathies.”

W. CAROE

Church Architect

From the Old Church visitor’s book:

“Inspiring and quite, I love coming here.”

“Beautiful”

“So peaceful”

“Cool and peaceful”

“It welcomes you as soon as you enter.”

[from: Penallt – A Village Miscellany]