The village school, just across the road from the bungalow, was a low building of grey stone with gabled windows and adjoined the village church, St. Mary’s. Rushton and Hilda had attended there when they were children and it was known as a Dame school. They showed me an old photograph showing a small group of children in the little front yard of the school wearing white pinafores, even the boys. “It be a bit different today with all those Brummies. And what with you Londoners, the school’ll be bursting at the seams!” exclaimed Rushton. “Never mind,” said Hilda, “Miss Jenkins will keep them all in order!” Who was Miss Jenkins and what were Brummies we wanted to know? Apparently Miss Jenkins was the formidable headmistress and the Brummies were the evacuees from Birmingham already arrived in the village a few months before. (image: Evacuees group, including Kath Price, in front of the school)

The village school, just across the road from the bungalow, was a low building of grey stone with gabled windows and adjoined the village church, St. Mary’s. Rushton and Hilda had attended there when they were children and it was known as a Dame school. They showed me an old photograph showing a small group of children in the little front yard of the school wearing white pinafores, even the boys. “It be a bit different today with all those Brummies. And what with you Londoners, the school’ll be bursting at the seams!” exclaimed Rushton. “Never mind,” said Hilda, “Miss Jenkins will keep them all in order!” Who was Miss Jenkins and what were Brummies we wanted to know? Apparently Miss Jenkins was the formidable headmistress and the Brummies were the evacuees from Birmingham already arrived in the village a few months before. (image: Evacuees group, including Kath Price, in front of the school)

Rushton and Hilda were the school and church caretakers. Rushton was responsible for opening up the school each morning and locking up at night, while Hilda kept the floor clean and polished the desks. In the winter Rushton lit the coke fired black iron stove at the top end of the main classroom. It had a chimney pipe going up through the ceiling and threw out a good heat. In fact, as we were soon to discover, there were only two classrooms. There was a separate entrance at the front to the infants’ classroom. Just along from this was the main entrance, through a stone porch, bringing you into a small cloakroom and the door to the big classroom. At the side of the cloakroom there was an arched wooden door, which led into the church vestry. The vicar sometimes made sudden appearances through this, showing his concern for the pupils’ spiritual welfare and making sure they were behaving themselves. The Birmingham children were in the majority. As I recall there were only about seven or eight of us Londoners, some evacuees from Folkestone with Penallt children making up the remainder.

Miss Jenkins was a strong featured, sturdy looking woman of indeterminate age. Everything about her gave the impression of strength from her thick wavy brown hair to her stout, sensible shoes. Her eyes were sharp and observant. She would not tolerate bad behaviour in her classroom and woe betide anyone who stepped out of line. She had been known to spank big boys across her knee and wash out their mouths with Lifebuoy soap if they used bad language. Gerald and I dreaded getting on the wrong side of her. For me, it was fine at first because I was in the infants’ class with Mrs Morgan, who was kind and motherly with a gentle, pretty face. She was known to all as Teacher Morgan and everyone loved her. She played the organ in church on Sundays while Rushton sat at the side pumping the wooden handle up and down to keep the accompaniment to the hymns going.

I was soon to discover that the Englands were regular church goers and attended church at least twice every Sunday (image: Penallt School and St Mary’s Church). This was a new experience for me. I don’t think I had ever been in a church before, my parents being agnostics. My Mum and Dad were good upright people all the same, concerned for the welfare of their fellow human beings. I have never been able to understand why being religious is supposed to make you into a good person. I really believe you can live a good life without believing in God. In fact, you have to try even harder without the crutch of religion to lean on. The Englands, however, were truly good and kind Christian people.

I was soon to discover that the Englands were regular church goers and attended church at least twice every Sunday (image: Penallt School and St Mary’s Church). This was a new experience for me. I don’t think I had ever been in a church before, my parents being agnostics. My Mum and Dad were good upright people all the same, concerned for the welfare of their fellow human beings. I have never been able to understand why being religious is supposed to make you into a good person. I really believe you can live a good life without believing in God. In fact, you have to try even harder without the crutch of religion to lean on. The Englands, however, were truly good and kind Christian people.

In church with the Englands that first Sunday was when I first set eyes on the vicar. He had an impressive sounding French name and must have been then in his early seventies. I was intrigued by his long white surplice and cassock and the sing song way he said the words in a high voice, not that I understood much of what was said. I loved singing the hymns, however, and recognized some of them from school. Auntie Hilda was an extremely good singer and managed to keep most of the congregation in tune, except for Lizzie Griffiths who sang loudly out of key in a deep toneless voice. She was a tiny figure dressed all in black with a black battered straw hat clamped firmly on her head. She always came to church with her brother, a rather sweet looking old man, not much taller than his sister with a white biblical looking beard. When I looked closer at Lizzie I noticed she had whiskers too but not as many as her brother. The vicar’s beard was trim, pointed and white matching his neat white hair. He had fine, aristocratic features, which gave him an air of superiority. His expression was cold and stern and I decided then and there that he was someone who wouldn’t want to have much to do with the likes of my brother and me and should be avoided at all costs. Rushton soon got into the habit of slipping me a humbug during the vicar’s sermons and then he would pop one into his own mouth and would suck on it noisily so that I had to stuff my handkerchief into my mouth to suppress my giggles. Auntie Hilda, sitting stiff and upright at the side of us would turn to look at us with a disapproving stare.

The church in those days was usually well attended. In fact it was of central importance to the social life of the village. The gentry from Moorcroft House were regulars – Mr del Sandys, J.P., an author of crime thrillers, his wife and sister-in-law. The ladies were always dressed elegantly in floating pastel shades and fashionable hats. I remember, even as a little one, admiring the way they were attired.

A little while later I was to discover there was another church in Penallt, which was used for services on the first Sunday of each month, and for weddings, funerals and christenings and special services at Easter and Christmas. Penallt Old Church, as it has always been called, never having taken the name of the unknown saint to which it is dedicated, is some distance from the centre of the parish. It is set on a sloping hillside above the River Wye and dates back to the 13th Century. It is a place of tranquillity and beauty and I have always loved it.

The first time I walked there with the Englands seemed like an adventure. We walked past the village shop and down the incline of a hill. We clambered over a wooden stile onto a footpath and then into an ancient wood, following a steep stony path bordered by large moss covered rocks until we came to another stile, which brought us onto a road opposite ploughed fields, the red earth stretching way up into distant woodland. “That be the footpath into town,” Rushton informed me pointing to a path through the field gate. “That’s the way I walked every working day to the Beacon offices.” I was soon to experience this walk but today was Sunday and we were heading for the church.

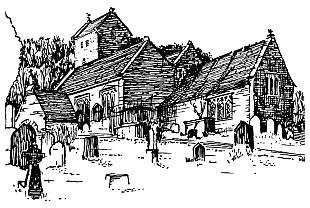

We turned right onto a quiet country lane, honeysuckle and woodbine clambering over the hedgerows, below which a bright profusion of wild flowers grew. I had never seen so many and longed to pick some but we had to be at the church for the eleven o’clock service and the Englands were never late. My little legs ached by the time we reached the wooden lych gate that led through to a lime tree walk up to the entrance of the ancient church (image: Penallt Old Church). We entered a stone porch with stone seats at either side. The church bell, loud and insistent, welcomed us in through the centuries old heavy wooden door. The gentry, who had arrived by car, had already taken their places in the long wooden pews. After them came the local folk. I can’t remember any other children being there, though some of the nearby farmers’ families must have attended. Teacher Morgan was playing appropriate music softly on a small organ, or it may have been a harmonium, as it had no pipes and didn’t need pumping like the church organ in the village. Everything so strange and new to me that day was soon to become comfortingly familiar, the musty smell of age, the quiet atmosphere, the stained glass window above the altar, the pulpit with the carved wooden eagle from where the sermons were delivered.

We turned right onto a quiet country lane, honeysuckle and woodbine clambering over the hedgerows, below which a bright profusion of wild flowers grew. I had never seen so many and longed to pick some but we had to be at the church for the eleven o’clock service and the Englands were never late. My little legs ached by the time we reached the wooden lych gate that led through to a lime tree walk up to the entrance of the ancient church (image: Penallt Old Church). We entered a stone porch with stone seats at either side. The church bell, loud and insistent, welcomed us in through the centuries old heavy wooden door. The gentry, who had arrived by car, had already taken their places in the long wooden pews. After them came the local folk. I can’t remember any other children being there, though some of the nearby farmers’ families must have attended. Teacher Morgan was playing appropriate music softly on a small organ, or it may have been a harmonium, as it had no pipes and didn’t need pumping like the church organ in the village. Everything so strange and new to me that day was soon to become comfortingly familiar, the musty smell of age, the quiet atmosphere, the stained glass window above the altar, the pulpit with the carved wooden eagle from where the sermons were delivered.

Towards the end of the summer, Rushton was responsible for cutting down the long grass and tidying the graves in the churchyard. This he did with a long, sharp reaper’s scythe. I loved to accompany him on these trips. In my memory, the weather was always fine and warm. Hilda would bring us a picnic, not forgetting Rushton’s bottle of cold tea and for me a bottle of Ballingers’ ‘pop’. I would spend the afternoon wandering up and down the sloping churchyard reading the inscriptions on the gravestones, some barely decipherable because of their great age. If a name particularly appealed to me, I would sit at the foot of the grave and talk to the person I thought was inside, especially if it happened to be a child. In my childlike way, I thought they could hear me and it would please them to have a friend and not be lonely anymore. What a strange little girl I must have been! On a clear day the view from the churchyard towards the valley, where the River Wye flowed between banks of verdant green alongside the narrow railway track, was an impressive sight. The river separated Wales from England. The villages on the other side of the river were in Gloucestershire and bordered the Forest of Dean, whose exciting woodland walks we were yet to discover. Towards Monmouth the steep hill of the Kymin rose up above the town, at the summit of which was a white temple celebrating Lord Nelson, one of the town’s famous historical visitors.

My brother, Gerald, took no part in our trips to the church. Penallt people attended either church or chapel. At that time there were two chapels in Penallt – the Baptist, which the Englands’ mason father had helped to build, and the older small Methodist Chapel, which was next door to Cartref. I don’t know what the difference was but chapel people went to both alternately and everyone attended the Baptist Chapel’s harvest festivals which were jollier than the church ones where the hymns were sung with gusto. I think the Porters’ were chapel by persuasion but not regular attenders and I think my brother had already decided that organized religion was not for him. In later years, visiting Penallt again, we would enjoy the walk to the Old Church. We would stop for a while to absorb the romantic atmosphere of the ancient graveyard and admire the splendid view across the valley. The place appealed to Gerald’s artistic senses. My mother and father fell in love with it when they first saw it. Now it is their last resting place.

[Next: Farming and the Bush Inn]

[Click here for overview]